Provisional Version

Profitability of the Universal Postal Service Provider

in a Free Market with Economies of Scale in Collect and Delivery

Prof. Dr. Gonzales d’Alcantara, University of Antwerp and Economic Expert

We propose a model for a liberalized

competitive postal market with a Universal Service Obligation Provider, the

Incumbent, and one Entrant. In this model we take into account the existence of

economies of scale in their collect and delivery activities. The study is

intended to lead to conclusions about the impact of economies of scale on the postal

market in various countries, as measured by the numbers of postal items

delivered per person and per year, and by the size of the population. We consider

delivery technologies of operators on markets of different sizes, measured both

by these two criterions. Variable and fixed costs in the collect and delivery

activities are determined by a structural cost model, which has the same form

for the Incumbent and for the Entrant. In this latter model we will also pay attention

to delivery technologies parameters which differ from country to country, such

as the number of delivery points per route stop. Given a definition of the USO,

assumptions about demand behaviour and the opening of the market to the Entrant,

the calibrated model will compute the impact of the cream skimming mechanism and

the graveyard spiral on volume, tariffs, market shares and the cumulative

balance of the Entrant needed to finance his delivery network. In a second step,

the model will also measure the effects of economies of scale on the financial requirement

of the Incumbent in charge of the USO, in case she keeps her tariffs at a

constant pre-competition level.

The existence of economies of scale has

been recognized in the literature… Key references are K. Jasinski and E.

Steggles, (1977), “Modelling letter delivery in town areas”, and, in various Michael A. Crew and Paul R.

Kleindorfer edited volumes, John

Panzar (1991), “Is Postal service a natural monopoly?”, Cathy Rogerson and William

Takis (1993), “Economies of scale and scope and competition in the Postal

services”, Michael Bradley and Jeff Colvin (1995), “An econometric model of

postal delivery”, Catherine Cazals, M. de Rycke, Jean-Pierre Florens, and S.

Rouzaud (1997), “Scale economies and natural monopoly in the postal delivery:

comparison between parametric and non parametric specifications”, Robert H. Cohen, and Edward H. Chu (1997),

“A measure of scale economies for postal systems”, Bernard Roy (1999), “Technico-economic

analysis of the costs outside work in postal delivery”.

All these references show the existence and importance of economies of

scale, which clearly exist in the delivery function and to a lesser extent in

other activities in the postal value chain. Our purpose is to examine the impact of these economies

of scale on the postal market in various countries. When the market opens and there are economies

of scale which differ country by country, what are the long term impacts of a well

defined regulatory set-up on tariffs, volumes and market shares in each case?

How do economies of scale affect the levels of the tariff differentials between

both operators? What

is the end-result in each country when scale obviously decreases for the

Incumbent with the entry of the competitor, who benefits both from increasing

scale and from relatively denser delivery zones, lost by the Incumbent? Which

parameters are crucial for the financial requirements of the Entrant, who wants

to invest in a delivery network, and for the Incumbent in charge of the USO,

when she keeps her tariffs at unchanged – affordable – levels?

The paper will treat two types of

model solutions:

a) The

regulatory authorities want to achieve a liberalized postal market without giving

any subsidies to finance the Universal Service Obligation of the Incumbent. The

Incumbent and the Entrant should behave as they would in a situation of

competition: both operators determine their tariffs according to their unit

costs including the margins to cover their fixed costs. The Incumbent therefore

modifies her tariffs so as to keep balanced or break-even accounts.

b) If the

Incumbent’s tariffs are required to remain equal to the costs per unit in the

base period before the market is opened, the starting situation under monopoly,

how large is then the financial loss of the Incumbent, provider of the Universal Postal

Service Obligation?

In this

contribution we will not take into account the possible inefficiencies of the

Incumbent, the obstacles to the access to the market by the Entrant or the

transition problems to go from an inefficient and monopolistic to a more

competitive market situation.

1.

The model

The postal market is modelled with two types of customers (j), retail customers and business customers. The retail customers are afforded special attention by the regulator because they have a high weight in social welfare. They are also characterized by more loyalty to the Incumbent and a less elastic demand than the business customers, who are more cost conscious. Both customers are assumed to consume one single product, for simplicity the same mix of first and second-class mail services.

There is an Incumbent operator (I) providing services for upstream and downstream. This operator has a Universal Service Obligation. This obligation includes delivering the whole population of the area to be serviced at least one time each day of the week (6 days). The tariff should be an affordable price; therefore tariff will be cost-based. No price-cap has been set-up. The tariff should be the same for all zones of delivery (tariff uniformity). The base period corresponds to a period with a reserved activity for the total volume.

In the first period, when the market is

opened, there is an alternative operator - the Entrant (E) - providing

competitive services for upstream activity and also able to provide downstream

activities. The downstream activity used to be the Incumbent’s reserved

activity in the base period, but it is opened to competition in the current

period. In other words, in the current period bypass is both technologically

and economically feasible for the Entrant.

Total market demand is related to broad

substitution possibilities for the customer among different forms of

communication. Since in the base period the Entrant is already providing

upstream services, new opportunities to create additional mail volume when the

conditions and regulations of the downstream activity are changed are not

likely. In the model, what is usually called the displacement ratio, s, will be

assumed to be equal to 1; i.e. for a given total market demand, an increase of

demand of one unit of the Entrant’s service necessarily leads to a decrease of

one unit in the demand for the Incumbent’s service. To summarize, within a

segment there is perfect substitution between the Incumbent and Entrant’s

services. No empirical evidence was found in the literature showing that the displacement ratio for the mail considered is

significantly different from 1.

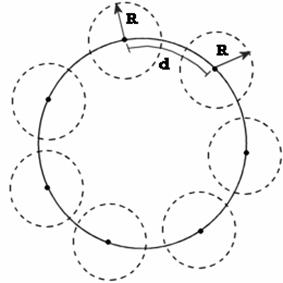

Each country is divided in two delivery zones, the dense or urban delivery zone (U) and the

non-dense or rural delivery zone (R). It is assumed indeed that dense zones are

situated in urban areas and non-dense zones in rural areas. Each of these

delivery areas is characterized by a grouping

index representing the number of delivery points per route stop, in

other words the average number of apartments in a building within the urban

zone for example. It is assumed that every delivery point (apartment) is

occupied by exactly one household, counting 2.6 people in the

Combining these elements, there are four different segments served by postal service providers: following the customers, where the market shares depend on customers behaviour, and following the density of delivery, where the market shares depend on unit cost differences.

a)

Demand

model

Exactly as d’Alcantara

and Amerlynck (2004), there are two steps in the demand model: the first is

related to possible substitutions and complementarities of Mail with respect to

other communication media on the broad market. The second is related to the

Mail customer’s behaviour, given the total mail volume he has determined as his

demand. The first is a constant elasticity demand model for total mail demand of a customer in a zone,

the second a market share model for each customer, determining the

substitution between postal service providers within customers’ market demand,

assumes two coefficients: a loyalty coefficient and elasticity. One defines a customer loyalty percentage as the percentage of the Incumbent’s

tariff that a given customer will accept to be higher than the Entrant’s tariff

without any decrease in his demand addressed to the Incumbent. Given the loyalty percentage of a customer and

given total market demand of this customer, the elasticity is the percentage change

of Incumbent’s volume demanded by this customer and strictly replaced by the

Entrant’s product, as a consequence of his percentage discount. Note that there

is one elasticity for each customer type, retail

and business, and for each destination, urban

and rural. The demand model consists of two sets of equations to be solved

simultaneously: a total market demand equation for each customer type and the

market share equations of the two service providers for their services provided

to the two types of customers in the two zones. The structure of these

equations is given in the Appendix.

The total market price elasticity of demand for postal services has

been assumed to be -.3. The value cannot be rejected in various econometric

studies of time series estimation surveyed by Catherine Cazals and Jean-Pierre Florens (2002).

At the stage of competing for the market shares, price

sensitivity of retail customers is relatively lower then that of business

customers. Retail customers are relatively more loyal to the Incumbent’s postal

service. The customer loyalty parameters ![]() are considered to be

20% for the Retail Customer and -10% for the Business Customer. The market share elasticity

are considered to be

20% for the Retail Customer and -10% for the Business Customer. The market share elasticity ![]() is lower for retail customers (-.75) than for business

customers (-1.25). The values of such elasticities are smaller in the case

there is a positive loyalty coefficient, which represents a lower tariff

sensitivity, and larger in the case there is a negative loyalty coefficient, which

represents a higher tariff sensitivity. We have taken the elasticity with zero

loyalty / disloyalty to be minus one. Such order of magnitude of the

elasticities for all mail categories should not be rejected, when looking

at the values found for first and second

class mail separately in various microeconometric demand studies, including

their own, surveyed by the same Catherine Cazals and Jean-Pierre Florens (2002).

is lower for retail customers (-.75) than for business

customers (-1.25). The values of such elasticities are smaller in the case

there is a positive loyalty coefficient, which represents a lower tariff

sensitivity, and larger in the case there is a negative loyalty coefficient, which

represents a higher tariff sensitivity. We have taken the elasticity with zero

loyalty / disloyalty to be minus one. Such order of magnitude of the

elasticities for all mail categories should not be rejected, when looking

at the values found for first and second

class mail separately in various microeconometric demand studies, including

their own, surveyed by the same Catherine Cazals and Jean-Pierre Florens (2002).

Figure 1 : Customer behaviour (market share model) : the Switching Function

b) Cost Model

The detailed cost model is presented in the appendix. It is an activity

based bottom up cost model. Scale is defined as the number of mail items per

person and per year. Population size is explicit in the model but was seen from

model solutions not to be significant as an additional size factor. The model

is mainly making the quantitative assessment of what is variable and what is

fixed cost, such as the park and loop delivery round. The fixed costs related

to the USO are central to assess the impact of postal market opening.

Services offered require an upstream activity, including collecting,

sorting and transporting, and a downstream

activity comprising delivering. Our downstream model is taking over the structure defined by Robert H. Cohen,

and Edward H. Chu (1997) for the USA and includes street model complements from

K. Jasinski and E. Steggles (1977), further applied by Bernard Roy (1999). The postal

activity model is divided in the collection, the sorting of the mail, the in-office

delivery, representing the sequencing of the mail into delivery routes, transportation

and the street delivery. The

street delivery decomposes itself into route travel, delivery access time and load

time. The route travel represents the walking or driving along the route

without stopping to delivery points. Route travel has 4 modes: Foot Delivery

(the cost of foot delivery depends only of the number of hour worked by the

carrier), Bicycle Delivery (the cost of bicycle delivery depends of the

hours worked by the carrier and of the maintenance of the bicycle), Park

& Loop Delivery (the cost of the Park & Loop delivery method

depends of the hours worked by the carrier and of the maintenance of the car)

and Car Delivery (the cost of car delivery depends of the hours worked

by the carrier and of the maintenance of the car). The delivery access time represents

the time to deviate from the route to access the delivery points. The load time

represents the time to place the mail in the mail receptacle of the delivery

points.

The fact

that each delivery area is characterized by different grouping indices representing the number of delivery points per

route stop has a considerable impact on the unit costs of delivery. The cost ratio between rural and urban zone

delivery precisely depends on this grouping index. This

cost differential is the driving element in the cream skimming mechanism. One assumes the average value of this parameter in the rural zone to be equal to 1, as a standard. This is

interpreted that in the rural zone one stop corresponds to a one family house. The average value of this parameter in the urban zone of the

The

When

introducing a country, we started with the

Delivery network: Delivery points per route: URBAN 488, RURAL 469. Grouping

index: RURAL 1 delivery points/stop. Delivery speed: foot 4 km/hour; bicycle 15 km/hour; park&loop car

35 km/hour. In between stop distance: foot 20 m; bicycle 100 m; park&loop car 300 m.

Vehicle cost ratio 0,02. Entrant delivery frequency 3 delivery/week.

Entrant starting geographic coverage: URBAN 10,0% RURAL 0,0%

c) The USO, Entrant’s

behavior and the dynamic tariff modeling

The Universal Service Obligation is one of the major exogenous factors

of the model we have constructed. We have defined the following USO to be

imposed by the Regulator on the Incumbent. This allows answering the major question

considered in this study, namely the impact of economies of scale on the postal

market in different countries. The USO is as follows:

i.

Daily distribution frequency (6

times)

ii.

Constant Quality (J + 1, J + n arrival

percentage, which is related to frequency)

iii.

Distribution to all customers

(retail and business, urban and rural zones)

iv.

Cost based tariff uniformity for

end-to-end and for access

v.

Affordable tariffs (interpreted

as keeping its present value for the Retail customers)

vi.

Availability (interpreted to be existence)

The Entrant is given the objective to

become the first market player and therefore to deliver as much mail as possible without

endangering his competitiveness. Therefore the Entrant

will invest in a delivery network, as long as his cost to deliver mail is lower

than the access tariff of the Incumbent. Between two periods, the Entrant has the

ability to decide to extend its delivery network or not. The new geographic

coverage of the Entrant delivery network will be equal to the collected market

share of the previous period. This justifies the

financial losses made by the Entrant during the first periods of entry. This

amount tends to zero when investment tends to zero and the cumulated amount to

be financed corresponds to the value of the capital needed to establish his

business. Note

that once the network has been extended, it is not possible to reduce it

afterwards. The Entrant does not have any Universal Service Obligation.

Entrant’s

behaviour is determined in the following way, all of the parameters being

parameters and can be

changed in the calibration:

i.

Distribution 3 times per week (different in quality level then

Incumbent)

ii. Same cost structure

and parameters as the Incumbent

iii. Uses self-employed at

50% of national hourly wage cost

iv. Different full cost

tariffs for dense and non-dense zones

v.

A starting investment in a delivery network in view of distributing in

the urban (dense) zones a share of 10% of the corresponding total volume of the

urban zone

vi.

Access to the Incumbent’s delivery network for the residual volume,

namely the volume

above his bypass potential

vii.

Invest in own delivery network, according to yearly decision made in advance,

an amount

capable to deliver the amount

collected in excess above his existing bypass capacity of the precedent period, only if his delivery cost

is lower than the access tariff of the

Incumbent.

Access pricing of the Incumbent is set at an access cost level, the average variable delivery cost including fixed costs plus a standard overhead. It would be possible to make a sensitivity analysis of the model results using a wider range of well-known access pricing methods, including those of the form that Michael Crew and Paul Kleindorfer and the Toulouse School have indicated as more efficient (of the DAP form).

The demand model is solved using iterative method. The model iterates until finding the market equilibrium. The competitive process starts with the entry of the competing operator and the dynamic tariff determination works as follows: The tariffs are set and fixed prior to the iterations. The demand of the previous period is the starting point. All tariffs are cost based. The Incumbent takes the total cost incurred in the previous period without the eventual cost of Entrant re-injection and considering the total mail volume collected in the previous period. The unit cost obtained is set as the Incumbent tariff of the current period. Like its end-to-end tariff, the Incumbent’s access tariff equals its unitary distribution cost, including the fixed costs and a general expense margin. The Incumbent satisfies tariff uniformity, both for end-to-end and for access. As the mail volume re-injected by the Entrant is not predictable by the Incumbent, it has been chosen to compute her end-to-end tariffs only taking into account her end-to-end volume. The unit cost of the Entrant is computed likewise but including the cost of re-injecting his mail in the Incumbent’s network and considering all his mail volume collected.

i. The

starting point is the monopoly situation: volumes per customer and per zone

ii. Cost

based tariffs are fixed by Incumbent, according USO and following equations

defined in Appendix

iii. The Entrant determines his volume

objective, unitary cost following the cost model (see

Appendix), tariffs per zone, volume delivery

objective and corresponding investment in his network

iv. Cream

skimming competition is simulated by the demand model. Equation (1) of the Appendix gives a new market average

tariff. The global mail demand is updated by the equation (2). Then total mail volume is computed. Then, a new value is obtained for ![]() from the equation (3).

The value

from the equation (3).

The value ![]() is the complementary

of the present demand

is the complementary

of the present demand

v. When

the market equilibrium is reached, the mechanism yields end of year volumes and

market shares

vi. On

the basis of the volume and market share results, the Entrant decides his

distribution network for next period. He wants to distribute what he was not

able to distribute and had to re-inject through access of the Incumbent’s

network a higher access tariff

vii. New cost based tariffs are set

viii.

Go to point iv, if % variation of one tariff or demand is higher then

convergence criterion e, this means as long as market equilibrium is not reached .

The calculation is stopped after 10 periods (i.e. 10 years), since it

marginal tariff changes become smaller then a small convergence criterion after

5 or 6 periods.

Clearly the

model describes the Entrant taking away mail through bypass: this erodes Incumbent’s

economies of scale in those zones in which bypass occurs. Such erosion

changes the volumes delivered by each operator in each zone and this determines

average costs of both operators, according to the zones in which bypass

occurs. The zone-specific impact of the Entrant is eroding delivered Incumbent

mail volumes, first in the dense low-cost zones, and therefore diminishes her

economies of scale and therefore leads to her tariff’s increase in view of

restoring her eroded profitability. In the case of the Entrant, the increase of

his volume decreases his unit cost because of increased economies of scale but

the increase of his volume in less dense zones increases his unit costs.

d) Results

Let’s first

summarize the assumptions made to calibrate our model about the standard

country, the customers, the competitor and the access regulation. One

introduces the number of items delivered per person and per year and the population

for the

Cost

elements: Urban area = 80 %. Labour cost per hour = 20,32 €. Retail ratio =

0,5. Delivery frequency Incumbent = 6. Household size = 2,6. Foot delivery = 6%.

Bicycle delivery = 0%. Park & Loop delivery = 39%. Car delivery = 55%. Exchange

rate € per dollars (2003) = 0,88... CPI (2003) = 1,40... Grouping index rural =

1. Grouping index urban = 2.

Retail and Business Customers: Market elasticity = -0,3. Retail loyalty = 20% Business loyalty =

-10%. Retail substitution = -0,75. Business

substitution = -1,25. Sigma = 1.

Competitor: Freelance cost ratio= 0,5. Delivery frequency Entrant = 3. E

starting coverage urban = 10% E starting

coverage rural= 0%.

Price regulation: Access pricing = accessed cost. Including other costs = Yes. Tariff

uniformity on access = Yes

With these

values the process converges. In a second step the values of the Mail delivery

Density are introduced corresponding to fixed intervals of 50. In this way one

obtains results corresponding to the sizes of most country: in each case the

model follows a process where scale obviously decreases for the Incumbent with

the entry of the competitor, and when the Incumbent looses dense urban zones

because of her high uniform tariffs. The Entrant benefits both from increasing

scale and from cream skimming the relatively denser delivery urban zones, lost

by the Incumbent. In Table 1. “Model Results per

Country Scale” countries are placed in view of the corresponding scales. After

5 or 6 periods the model always converges, but the period reported is period

10. One should not interpret these results as final values for the countries

since the calibration of the data used should still be considerably improved.

However the large variations obtained in the results are of interests to

understand the impact of economies of scale.

1° Solutions

with break-even tariffs for the Incumbent

When

the market opens and with the definition of the USO, what are, according to economies of scale which differ country by country,

the long term impacts

on tariffs, volumes and market shares? These

variables of the converged model result are shown following the number

of mail items per person and per year.

§ Unit cost variation under monopoly (unit cost

= 1 for

The cost curve is non-linear. While the medium

size countries

|

gU = 2 |

|

|

Austria-France |

Finland-UK |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Scale |

1,00 |

0,85 |

0,70 |

0,55 |

0,45 |

0,30 |

0,25 |

0,20 |

0,15 |

0,08 |

|

Unit costs |

1,00 |

1,04 |

1,10 |

1,19 |

1,29 |

1,56 |

1,71 |

1,95 |

2,35 |

3,76 |

Graphically

presented, one has

Figure 2 : Standardized Unit Cost in function of Scale

§

Incumbent tariff variation after competition (Incumbent

tariff after competition convergence divided by Incumbent tariff under

monopoly)

The tariff increase to be introduced by the

Incumbent as a consequence of the arrival of the Entrant, her loss of size and

of less costly urban zones, results to be relatively important, but much more

so in small size countries: the USA tariff increases by 53% while the French

one increases by 72% and the Italian increases by 126%. This corresponds to the

price the retail customer has to pay for the USO after the opening of the

market.

§

Entrant Urban and Rural tariffs after competition (Entrant tariff in

Urban and Rural areas after competition convergence divided by Incumbent

uniform tariff under monopoly)

The discount given by the Entrant is considerably

higher in small size countries then in large size countries: extremes vary with

66% against 39% in the Urban zones and with 36% against 29% in the Rural zones;

this also reflects a relatively more aggressive behavior of the Entrant in the

Urban zones of the small countries. Scale is less significant in Rural zones

because higher unit costs prevents the Entrant to capture market share.

§

Total volume variation after competition (volume

after competition convergence divided by volume under monopoly). The impact of

competition on reduced average tariffs and on general communication market

substitution is positive and stronger in small scale countries, the extremes

varying from a 10% increase to a 25% increase.

§ Entrant Collect

market shares on Retail customers after competition

Retail markets are more difficult to be

captured by the Entrant then Business markets because of the loyalty of the

customers and their lower tariff sensitivity, but small size again is

relatively more dangerous for the Incumbent: in the smallest country the

Entrant captures 48% of the Retail market share for a 66% discount in the Urban

zones and a 36% discount in the Rural

zone against 29% in the USA for a 39%

discount in the Urban zones and a 29%

discount in the Rural zone.

§ Entrant Collect

market shares on Business customers after competition

Business markets are much easier to be captured

by the Entrant then Retail markets, because of the readiness of business

clients to switch to the Entrant and their higher tariff sensitivity. In small

size countries total 100% market share goes to the Entrant. In the large ones

the Incumbent only keeps 14% of the business market. Clearly the business market

structure has turned upside down with the assumptions made. It is

understandable, because, from a methodological point of view, when in reality a

50% market share is reached, there is a duopoly: it is not possible to keep our

same model assumptions about the market structure and parameters. For example,

a game theoretic model should be used. The Entrant’s labor cost discount

assumed would not be realistic. No further study was done about this.

§

Financial resources needed by Entrant to invest into his own

delivery network after competition (Entrant’s cumulative profit or account

balance after competition divided by Entrant’s revenue after competition). It

is interesting to see the impact of the market opening on the financial

resources needed by the Entrant to invest into a delivery network: it is

obviously related to the importance of the delivery network he has created to

take over a high delivery market share from the Incumbent. In the case of